Lumbar Puncture Spinal Tap

A lumbar puncture is used to diagnose meningitis and some other brain and spinal cord disorders.

Note: the information below is a general guide only. The arrangements, and the way tests are performed, may vary between different hospitals. Always follow the instructions given by your doctor, specialist, or local hospital.

What is a lumbar puncture?

A lumbar puncture (sometimes called a spinal tap) is a procedure where a sample of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is taken for testing. CSF is the fluid that surrounds the brain (cerebrum) and spinal cord. This test is most commonly used to diagnose meningitis (an infection of the meninges - the structure that surrounds the brain and spinal cord). It is also used to help diagnose some other conditions of the brain, spinal cord and central nervous system, including a subarachnoid haemorrhage which is a type of bleed inside the brain.

When is a lumbar puncture needed?

If you, or your child, is admitted to hospital with symptoms that could be caused by meningitis then a lumbar puncture may be done urgently, either in the emergency department or very soon after your admission to a ward. Alternatively, you might be admitted for a planned lumbar puncture, as part of the diagnostic process for a long-term (chronic) neurological condition.

How is a lumbar puncture done?

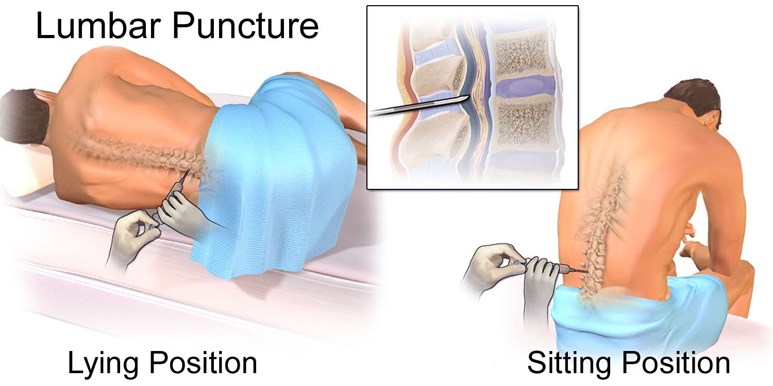

Usually you lie on a couch on your side with your knees pulled up against your chest. Sometimes it is done with you sitting up and leaning forwards on some pillows. The doctor or nurse will clean an area of your lower back with antiseptic.

They will then inject some local anaesthetic into a small area of skin which lies over a space between two lower spinal bones (vertebrae). This stings a little at first but then makes the skin numb.

The doctor then pushes a thin hollow needle through the skin and tissues between two vertebrae into the space around the spinal cord which is filled with CSF. Because the skin is numbed with local anaesthetic, most people do not feel pain. You may feel pressure as the needle is inserted. However, some people do have a sharp feeling in the back or leg when the needle is pushed through.

Procedure method

By Blausen.com staff, "Blausen gallery 2014", Wikiversity Journal of Medicine, via Wikimedia Commons

Some fluid leaks back through the needle and is collected in a sterile pot. If you have possible meningitis, this fluid sample is sent to the laboratory to be examined under the microscope to look for germs (bacteria), red blood cells and white blood cells, which are a sign of infection. It is also 'cultured' to see if any bacteria grow and what type they are.

The fluid can also be tested for protein, sugar and other chemicals if necessary. Sometimes the doctor will also measure the fluid pressure. This is done by attaching a special tube to the needle, which can measure the pressure of the fluid coming out.

The needle is usually in for about 1-2 minutes. As soon as the required amount of fluid is collected, the needle is taken out and a sticking plaster put over the site of needle entry.

How long does a lumbar puncture take?

In total the procedure will take about 30-45 minutes; this includes the time to get you ready in the correct position and set up all the equipment.

Are there any side-effects or risks from a lumbar puncture?

Some people develop a post lumbar puncture headache. This usually goes after a few hours. It is best to lie down for a few hours after the test, as this makes a headache less likely to develop. There is also risk of infection or bleeding at the needle puncture site and although rare, some damage to the spinal cord or brain may occur as a result on a lumbar puncture. It is very important that you tell the doctor if you are taking anticoagulants (blood-thinning drugs) so that they can take any necessary precautions to reduce the risk of bleeding.

Recovering from a lumbar puncture

It is sensible to stay lying flat for a period of time after a lumbar puncture - the doctor who does it will tell you how long. They will usually advise you not to operate heavy machinery or drive for at lest 24 hours and not to play sport or do any strenuous activities for at least a week.

Further reading and references

Bacterial meningitis and meningococcal septicaemia: Management of bacterial meningitis and meningococcal septicaemia in children and young people younger than 16 years in primary and secondary care; NICE Clinical Guideline (last updated February 2015)

Sepsis - recognition, diagnosis and early management; NICE Guideline (July 2016 - updated September 2017)

Meningococcal disease: guidance, data and analysis; UK Health Security Agency (last updated April 2022)

Viallon A, Botelho-Nevers E, Zeni F; Clinical decision rules for acute bacterial meningitis: current insights. Open Access Emerg Med. 2016 Apr 198:7-16. doi: 10.2147/OAEM.S69975. eCollection 2016.

Cognat E, Koehl B, Lilamand M, et al; Preventing Post-Lumbar Puncture Headache. Ann Emerg Med. 2021 Sep78(3):443-450. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2021.02.019. Epub 2021 May 7.